Emerging market equities delivered stellar returns for much of the noughties. With the Chinese economic miracle at the forefront, we witnessed a prolonged period of strong economic growth, fast-growing domestic consumption and appreciating currencies. And, after the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, investors began to wonder whether the emerging market story might even prove resilient enough to withstand the economic turmoil in which the developed world found itself embroiled.

Yet fast-forward to the summer of 2015 and sentiment towards emerging markets has shifted markedly following three years of weak performance and depreciating currencies. Over the three years to August 2015, the MSCI World index has delivered a total return of 45% in sterling terms, whilst the MSCI Emerging Markets index has fallen by 3%.

So what has the problem been?

With regards to the poor performance of emerging markets, two main factors must take the blame. First, the Chinese economic powerhouse is stalling. A slowdown in the growth of the working age population and rising real wages has seen China begin to lose competitiveness versus other global manufacturing bases and this, coupled with the weak export demand from the developed world and a strong currency, means that the country is no longer able to rely on net exports to drive growth.

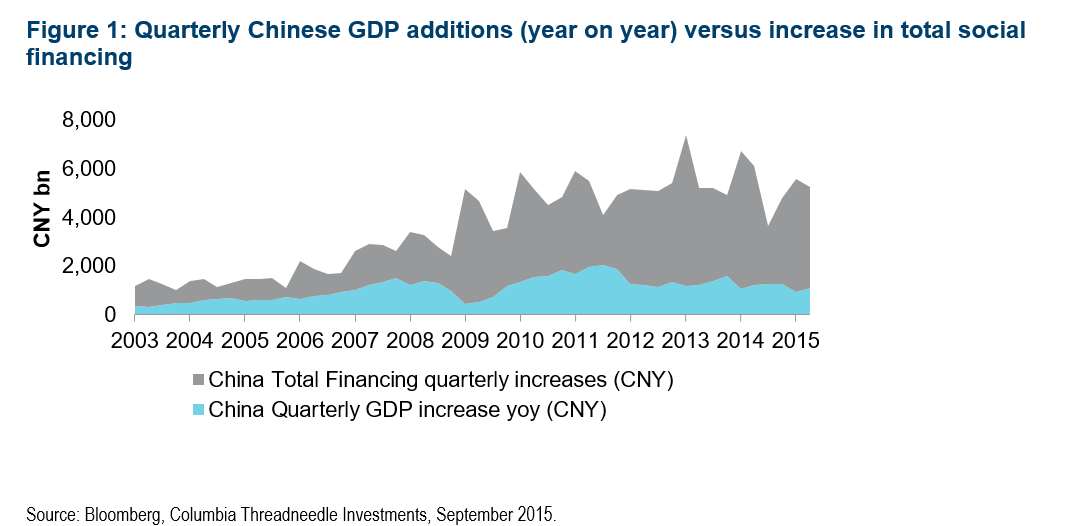

For several years, the Chinese authorities were able to offset this with a massive programme of infrastructure spending and by allowing loose monetary conditions to fuel a domestic property boom. Now, however, the rapid increase in local government and corporate debt has made this alternative path unsustainable ( Figure 1 ). Hence the switch in focus by the Chinese authorities to a third path: creating a domestic demand-driven growth model more similar to Western economies.

But this process of transition is a slow one and, moreover, it is made all the more complicated by the previous cycle of overinvestment which has supressed corporate profitability and left many companies with weak balance sheets.

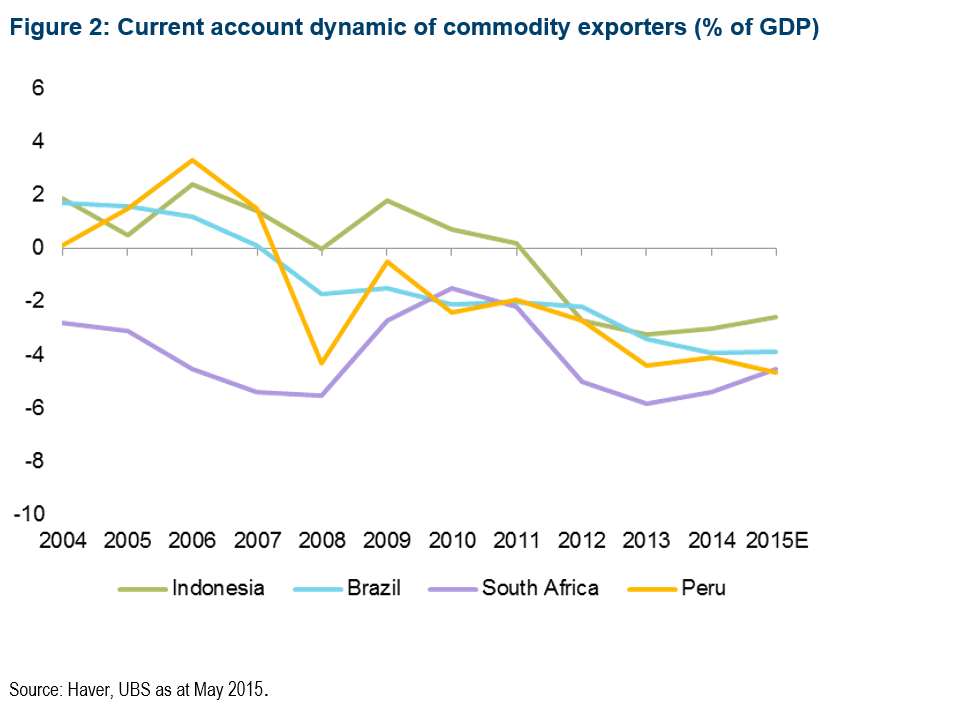

A problem for China, of course, but also a problem for those emerging countries whose growth was previously fuelled by China’s voracious appetite for their natural resources, driven by the aforementioned boom in property and infrastructure. Countries such as Brazil and South Africa now find themselves with a deteriorating trade balance ( see Figure 2 ) which has increased their dependence on foreign capital inflows to fund their own demand for imports.

The second major factor is that emerging markets remain vulnerable to the ebb and flow of global liquidity which, in the era of quantitative easing ( QE ) and close to zero interest rates in the developed world, has proved all the more dramatic. The US Federal Reserve launched its QE programme in 2008 to stimulate the US economy and ward off the threat of another Great Depression. However, QE also drove down the return investors could obtain from assets such as government bonds.

Consequently, some sought more profitable opportunities elsewhere, including in emerging markets, resulting in very large inflows to fixed income and equities. However, this left emerging markets vulnerable to the eventual tightening of monetary policy, a fact which was brought into sharp focus by the ‘taper tantrum’ in the summer of 2013 when markets woke up to the reality that many emerging markets ( EMs ) were running large current and fiscal deficits, funded by foreign capital.

What followed has been more than two years of painful adjustment as EMs prepare for the eventual tightening of US monetary policy. This process has been seen in depreciating currencies as fixed income investors reduce their exposure to EM countries' debt. Perhaps more significantly, however, it has also had serious consequences for domestic economies as central banks have had to allow an increase in domestic real interest rates, forcing a contraction on the domestic side of their economies as well.

So far, so painful. Having diagnosed the patient, are there any signs of recovery?

The good news, we believe, is that for many emerging markets, much of the necessary rebalancing has taken place now. Current account and fiscal balances look more sustainable, particularly in oil-importing countries. Crucially, real rates, i.e. the returns offered to investors to fund the deficits that remain, are now firmly in positive territory.

Nevertheless, progress has not been uniform and we remain cautious on the outlook for EM commodity exporters who, we believe, will continue to see their terms of trade under pressure. On the other hand, we feel most positive about countries, such as those in the CEE region, that have seen the most dramatic improvement in their fiscal and external balances. Most importantly, with the first interest rate hike by the Federal Reserve now expected within the next six months, we believe that the EM asset class looks in a much better position to withstand the resultant tightening in global liquidity.

Be aware of the danger – but recognise the opportunity

The political landscape in emerging markets has been challenging recently. However, in certain countries we have seen economic necessity result in positive political outcomes. Here we would highlight markets such as Mexico and India which have investor-friendly governments with mandates for reform. In these countries policymakers are not merely accepting the economic adjustments forced on them by debt-market dynamics, but are taking the opportunity to implement far-reaching structural reforms that should put them on a more sustainable economic path in the future.

Where we are most constructive is India where last summer Narendra Modi and the pro-business Bharatiya Janata Party ( BJP ) swept to victory on a platform that promised to tackle many of the barriers to investment in the country. Of particular focus have been removing bureaucratic hurdles, addressing the corruption that is endemic is certain sectors of the economy and pushing through a much-needed programme of infrastructure investment. If successful, we believe these measures will lead to a step change in the growth rate of the Indian economy.

Mexico too has an encouraging reform programme of its own. President Enrique Peña Nieto, who was elected in the summer of 2012, has been pushing through a series of laws to increase flexibility in the labour market and to open up the country to more foreign investment, particularly in the energy sector where there are hopes it will unlock some of Mexico’s enormous potential in deepwater oil and shale gas.

Even in China, although we remain concerned by the scale of the task facing the authorities to rein in the reliance on debt creation for economic growth and to offset the impact of the slowing construction sector, there are nevertheless positive noises about reform. In particular, reform of the SOE sector is taking place and there is a shift away from the polluting and low-value added industrial sectors such as steel and chemicals.

The long-term case for emerging markets

Finally, investors should never lose sight of the structural growth drivers that have long made emerging markets an attractive area in which to invest and which remain as compelling as ever. At the centre of these is the rapidly expanding middle class, eager to enjoy a higher standard of living and consume a wider range of goods and services. For this reason, we believe that areas such as healthcare, e-commerce and modern food retail formats remain extremely attractive areas for investment.

It will pay to differentiate in EMs

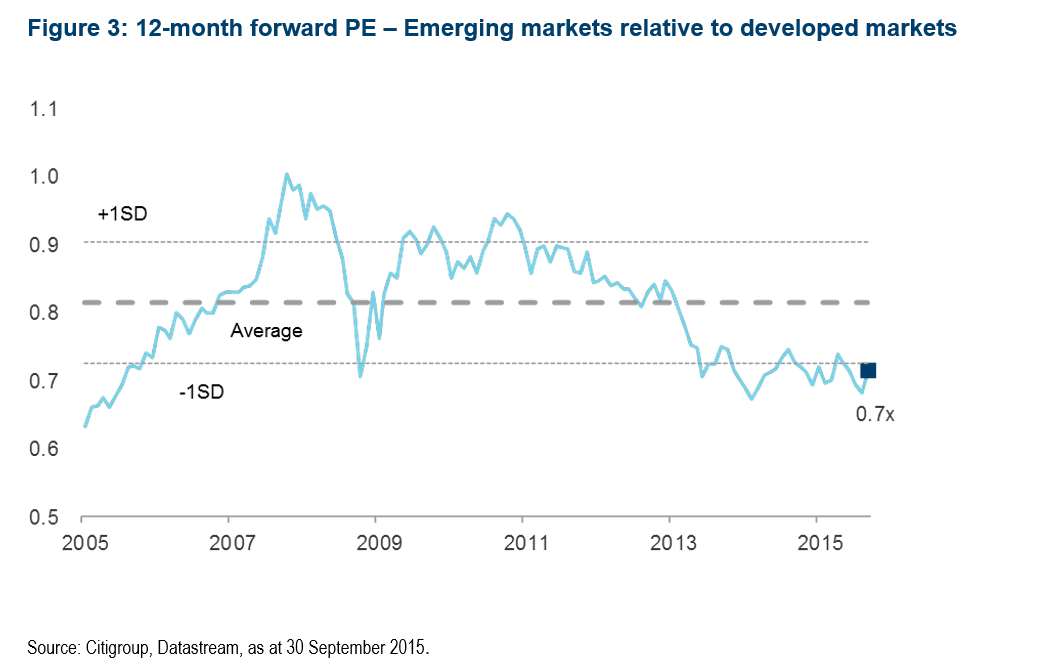

On headline numbers emerging markets have looked cheap versus developed market for quite some time ( Figure 3 ), but this was not enough to make a case for the asset class in the face of several years of growth and earnings disappointments. Now, however, we seem finally to be at a point where we can start to build a more compelling case for investing in emerging markets. With yields and currencies offering significant value to foreign fixed income investors, the EM asset class now looks much more resilient to higher US interest rates. Moreover, for those countries which are furthest through the rebalancing process, the pressure on domestic economies should, we believe, start to abate.

However, this asset class is anything but homogeneous and now more than ever it pays to differentiate between those countries that have made the most progress in tackling economic imbalances and setting themselves up for stronger and more sustainable growth in the future and those where there is more to do. As a result, the opportunity for active investors to seek out higher returns looks better than ever.

This is why we remain focused on those markets where progress has been greatest and those companies which are best-positioned to benefit from these reforms. The good news is that there are an increasing number of world-class companies to choose from, with capable management, healthy balance sheets and strong cashflow generation. For active investors, emerging markets remain rich with opportunity.

Georgina Hellyer is portfolio manager at Columbia Threadneedle